Journal

Do Plant Dyes Fade? Two Chair Seats, 100 Years Apart

The first question people ask about botanical dyes is whether they fade.

My answer: yes, they do. All dyes fade. But if you prepare your fibres properly and choose your plants sensibly, natural dyes will not fade any more than most synthetic dyes. Often they’ll fade considerably less.

Here’s the evidence from my collection.

The 18th Century Piece: 1760s-1790s

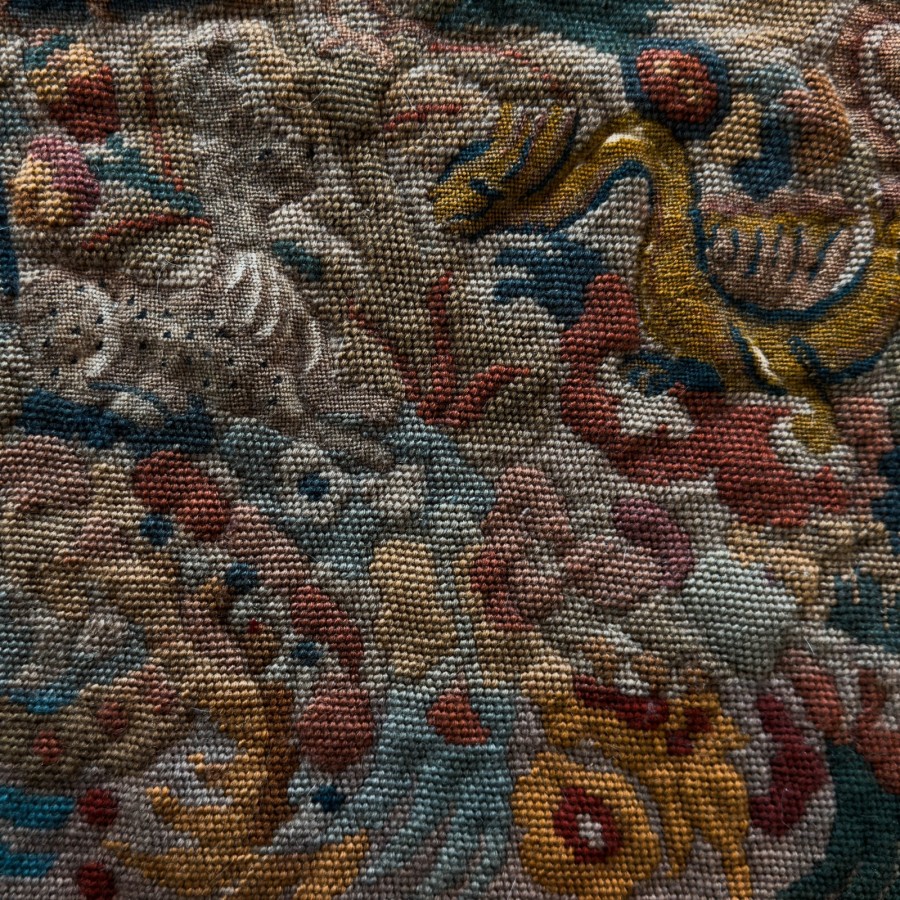

This needlepoint was made as a chair seat, probably between 1740 and 1770. It’s worked in plant-dyed wool on even-weave linen - petit point at 22 stitches per inch for the animals, tent stitch at 11 stitches per inch for the background.

This was a working chair seat. It wasn’t wrapped in tissue and kept in a drawer. It was sat on, used, eventually removed from the chair when it wore out or the furniture was updated.

It’s approximately 250 years old.

When you compare the front and the back, you can see some fading - the colours have lightened. But they haven’t changed. The blues are still blue, the rusts still rust, the greens still green. The colour relationships remain intact. You can still read the design clearly.

The silk stitches have disappeared almost entirely - silk is more vulnerable to wear than wool - but the wool has survived with its colours stable.

The 19th Century Piece: 1860s-1880s

This is Berlin woolwork, probably made between 1860 and 1880. It came from a prayer chair, worked on the new double-thread canvas that made following printed patterns easier for amateur needleworkers.

It’s dyed with early aniline dyes - synthetic dyes that were revolutionary when they arrived. Bright turquoises, sharp vermilions, colours that were difficult or impossible to achieve with natural dyes.

The bottom section was hidden in the chair structure and never saw daylight. You can see what those colours originally looked like - that intense turquoise, those vivid reds.

The exposed section tells a different story. Everything has faded to murky beiges and washed-out pinks. The colour relationships have collapsed. The design is harder to read.

This piece is roughly 150 years old - a full century younger than the plant-dyed chair seat.

What This Tells Us

The problem with early aniline dyes wasn’t that they were synthetic. It was that the dyers hadn’t yet figured out lightfastness. They were chasing novelty and brightness, not durability. Contemporary accounts mention these dyes fading after a week in a shop window.

The 18th century chair seat was made by someone who expected it to last. Proper mordanting, stable dye plants, good materials. The dyer knew what they were doing.

The Practical Takeaway

Fading isn’t about natural versus synthetic. It’s about technique, mordanting, and choosing stable dyes.

The workhorses of 18th century dyeing - indigo, woad, madder, weld - were stable precisely because they’d been refined over centuries of use. Dyers knew how to prepare fibres properly, which mordants to use, which plants gave lasting colour. Many other plants, local plants, are fantastic dye plants too. The difference isn’t the plant, it’s the preparation.

If you’re working with botanical dyes now, you have access to that accumulated knowledge. Proper mordanting, good fibre preparation, and careful technique will give you lasting colour from all sorts of plants. Start with what’s growing around you. Use mordants. Experiment and take notes. The colours will last.

You may also enjoy …

Making tea-lights

3 years ago

Dyeing cotton yarn with nettles

How to dye cotton yarn with nettles, natural dye

4 years ago

The herbarium project

inspiration vintage herbaceous on my eco printed textiles

2 years ago

Bundle dyeing yarn: a November experiment

Yarn bundled with leaves, frost on the hedgerows, observing the small transformations of late autumn.

2 months ago