Journal

What Remains: Looking at the Things People Actually Used

Last Sunday, I sat in an archive room with a 16th-century nightshirt spread in front of me. Twenty minutes, just looking. The archive assistant had shown me how to wash my hands properly, how to handle the fabric, and then left me alone with this thing that had clothed someone’s body hundreds of years ago.

It wasn’t pristine. That’s why I’d chosen it.

Most museum collections preserve the best of things - the ceremonial robes, the unworn wedding dress, the sampler framed and protected by seven generations of careful daughters. These objects tell us about aspiration, about wealth, about what people thought worthy of keeping. But they rarely tell us about Tuesday afternoons or mending by candlelight or the third time you patched something because cloth was too precious to discard.

This shirt told a different story.

What We Don’t Usually Get to See

The V&A’s new storehouse in east London has done something quietly revolutionary. Instead of keeping their vast collections locked away - the usual museum problem where 95% of holdings never see daylight - they’ve opened the stores to anyone who wants to book an appointment. No academic credentials required. No research proposal. Just curiosity.

I went online, scrolled through their catalogue like a particularly sophisticated version of window shopping, and selected five objects. Four were early embroidered bags for research - we’re making bags in The Studio this month, and I wanted to see what real medieval and Renaissance pouches actually looked like, not the romanticised Pinterest versions. The fifth was this shirt.

The V&A catalogue described it simply: linen, silver thread embroidery, handmade lace inserts, probably late 16th century. What the catalogue didn’t say - what catalogues never quite capture - was that someone had loved this thing enough to keep mending it long after it stopped being beautiful. Patching, altering, reusing

The Evidence of Use

Both cuffs had been patched, where the wearer’s wrists had worn through the original embroidery. The patches used similar silver thread but in slightly different patterns - perhaps done years apart, perhaps by different hands. The underarm gussets had been replaced entirely, more than once. There was a hole at the front that had never been mended, and a dark stain on one sleeve that might have been blood.

This was a high-status garment. The quality of the original work, the silver thread, the fine linen - this belonged to someone with means. But it had been worn, properly worn, the kind of wearing that requires maintenance and repair. And someone - we don’t know who - cared enough to keep mending it.

I kept thinking: what would it take for something like this to survive 400 years? Someone had to decide it was worth keeping even after it was too damaged to wear. Someone else had to store it carefully. Multiple someones had to choose not to discard it, cut it up for cleaning rags, or let it moulder in a damp chest. And eventually, someone had to give or sell it to a museum.

Most things don’t survive. Most of what people made and used and wore out is simply gone. What remains is either the too-precious-to-use or, more rarely, something like this - precious enough to keep but used enough to show us what real life looked like.

Maureen’s Exercise Book, 1947

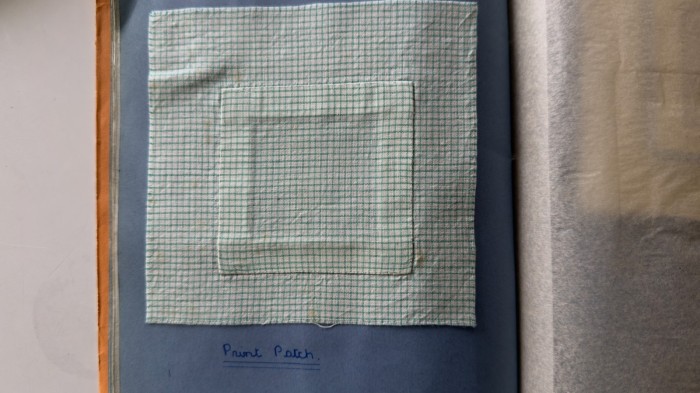

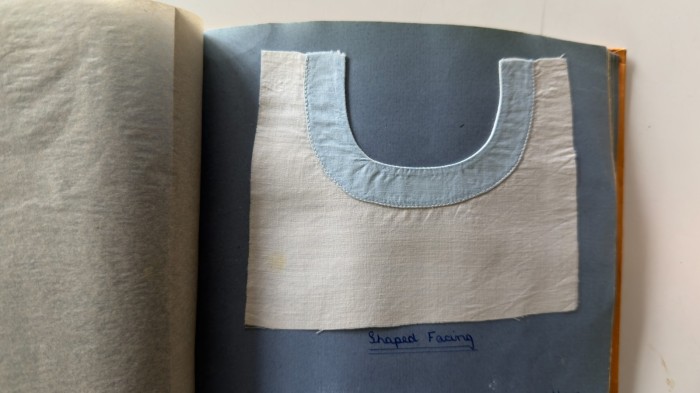

When I got home, I pulled out something I’d bought on Vinted last month: a sewing exercise book from a finishing school, dated 1947. The young woman who made it - Maureen Bushell - had filled it with samples. Hemming, darning, inserting gussets, making buttonholes, patching knees, all the skills that would have been considered essential for a woman of her time.

1947 is an interesting year to be learning these skills. The war had been over for two years, but Britain’s economy was in tatters. Clothing rationing, which had begun in 1941, had actually intensified. Each person got 66 coupons a year, and a dress cost 11 coupons, a blouse 5, a pair of stockings 2. Women’s magazines ran endless features on making do and mending, turning old coats into skirts, unpicking jumpers to reknit them in fashionable styles.

So Maureen, at finishing school (which suggests her family had some means), was learning skills that had suddenly become relevant again across all social classes. The ability to darn invisibly, to patch neatly, to alter and remake - these weren’t genteel accomplishments anymore. They were survival skills.

What strikes me about her samples is their skill. This is work that would have been considered merely adequate at the time - I’ve been told she regarded herself as a mediocre needlewoman - but it’s far beyond what most of us could do now. The tension is even, the stitches regular, the corners properly mitred. This was baseline skill, what every woman was expected to master.

Seventy-seven years later, so many of us couldn’t darn a sock if our lives depended on it.

Why Looking Matters Now

There’s something that happens when you spend real time with a handmade object. Not glancing, not photographing for Instagram, but actually looking. Twenty minutes with the nightshirt. An hour with Maureen’s exercise book, turning pages slowly, noticing where her stitching gets tighter or looser, where she’s made a mistake and corrected it, where you can almost feel her frustration or satisfaction.

You start to see the hands. You start to notice mood - the careful sample done when she was fresh, the slightly rushed one done at the end of a long day. You see decisions: where to start the patch, which direction to run the darn, whether to unpick and redo or just carry on.

This kind of looking is harder than it sounds. We’re trained to glance and move on, to consume images quickly, to form instant opinions. Sitting with one object for twenty minutes feels almost transgressive. Your mind wanders. You get restless. You think you’ve seen everything there is to see.

And then, if you keep looking, things begin to reveal themselves. The nightshirt’s bloodstain becomes a person’s wound. The patched gussets become evidence of someone’s decision that this was worth saving. Maureen’s ever so slightly wobbly hemstitch becomes the hand of a young woman learning, probably bored, possibly hungry (1947 had food rationing too), definitely not imagining that seventy-seven years later someone would be looking at her work and thinking about her life.

An Invitation

You probably have something in your home that deserves this kind of attention. Something handmade, handed down, or made so long ago it almost feels like someone else made it. Find it. Clear some space. Turn off your phone. And just look.

Look past what you think you already know about it. Look at tension in stitches, mistakes corrected or left visible, places where the maker changed their mind or persevered despite difficulty. Look at wear patterns, stains, repairs. Look until you can almost feel the hands that made this, the mood they were in, the decisions they made.

This isn’t precious or spiritual - though it might feel like both. It’s just the kind of attention that handmade things have always deserved and rarely received. The kind of looking that connects us back through time to all the people who made and mended and kept things going, whose names we mostly don’t know, whose work mostly didn’t survive.

But some of it did. And it’s still here, waiting to be really seen.

Visit the V&A Storehouse: You can book appointments online - remarkably underused and absolutely worth the trip

Join us in The Studio: This season we’re making bags inspired by Irish traveller tales.

You may also enjoy …

Crewel work fragment from Jacobean Bed hangings: What You Can Still See After 400 Years

Close look at a crewelwork bed curtain from 1610-1620: which colours survived 400 years, how designs were transferred, and why these mattered.

2 weeks ago

Using pressed leaves to decorate gift wrap

pressed leaves decorating natural gift wrap.

5 years ago

Botanical Dye Plants: Gorse

Explore the story of gorse — from a symbol of Scottish crofting to a vibrant natural dye. A personal reflection on heritage, migration, and the soft yellow hues of spring.

8 months ago

Making calendula tea

making a calendula tea

4 years ago