Journal

What Andy Goldsworthy’s Ferns Taught Me About Seeing

I stood there for longer than I probably should have, trying to capture what Goldsworthy had seen - the way these ferns wanted to curve, the particular shadow each frond cast, the rightness of their arrangement. This is what he does, what he’s always done: he sees what’s already there, waiting to be arranged. Not imposed on. Arranged.

And I think this is why his work matters so much to those of us who gather and make. He’s showing us that the materials themselves have wisdom. That our job isn’t to force them into shapes they don’t want to take, but to see what they’re already offering.

Inside The Studio, we’re exploring this kind of seeing through Threaded - gathering natural materials, making felt beads, learning to work with what each material offers rather than forcing it into predetermined shapes. It’s gentle, seasonal work. The kind Goldsworthy would recognize.

Rag Rugs, Remembered: Creativity, Memory, and the Quiet Legacy of Women’s Work

There’s something deeply evocative about a rag rug.

For me, they conjure childhood memories—of my gran cutting up old clothes in her Northeast home, of hands busy at the hearth as winter crept in. Every year, she’d make a new rug. Not as art, but as necessity. And yet, looking back, it was art. Quiet, domestic, fiercely resourceful art.

Rag rugs are humble. Scraps turned into something sturdy, beautiful, and useful. And lately, my fingers have been itching to make one. Partly due to the powerful exhibition I saw recently—Winifred Nicholson: Cumbrian Rag Rugs at the Tullie Museum in Carlisle—and partly because I’ve inherited my gran’s rug frame. A piece of family history, waiting to come alive again.

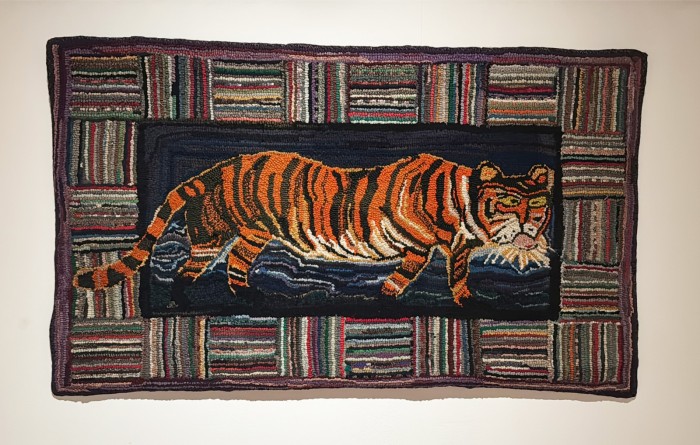

Tiger, worked by Janet Heap early 1960s

A Different Kind of Creativity

The exhibition explores how Winifred Nicholson—a respected artist—collaborated with rural Cumbrian women from the 1920s through the 1980s to create striking rugs. Though Nicholson provided loose design ideas, the true artistry lay in the hands of makers like Mary Buick. Her work, full of precision and pictorial nuance, told stories through stitches. Yet in art history, her name is often lost behind Nicholson’s.

This discrepancy matters.

It reflects how society has long undervalued women’s domestic creativity. Rug-making, quilting, embroidery—seen as craft, not art. Functional, not visionary. And yet, these works were acts of deep care, resourcefulness, and yes—creative genius.

Sheep, worked by Mary Bewick to design by Winifred Nicholson 1960s

Making With What You Have

British rag rugs evolved from scarcity. No pre-planned palettes or bought-in fabrics—just old coats, worn sheets, a t-shirt you no longer needed. In the Northeast, these were called clippy mats or proggy rugs, and they followed simple geometric designs. My gran always used diamonds—drawn on old hessian sacks, filled in with whatever colours were on hand.

In contrast, American traditions turned rug making into a designed-from-scratch craft. But in the UK, it was about making do. And in that “making do,” women made beauty.

Tractor and Haycart, worked by Mrs Hall to design by Jovan Nicholson 1967

Creativity as Reclamation

Watching the exhibition’s rugs—some damaged, worn, obviously lived with—was unexpectedly moving. They hadn’t been preserved behind glass. They’d been stepped on, warmed toes, sat beside fires. They were loved, and used, and that’s part of their magic.

It reminded me that creativity doesn’t need polish. It needs space. Time. Willing hands.

And it reminded me that our making—however small or irregular—is a way of reclaiming ourselves. Especially for women whose time, historically and still, has so often been claimed by others.

What’s Next

I’ll be making my own rug soon. I don’t have long strips of wool, so it’ll be a clippy mat—shaggy, abstract, full of texture and colour. I’ll be working with what I have, like my gran did. Like so many did.

If you’ve made a rug, or remember someone who did, I’d love to hear. If you’ve been to the exhibition, let me know what stayed with you. Creativity is always richer when it’s shared.

Finding Time to Make: What Barbara Hepworth Taught Me

About 15 years ago, we rented an Airbnb in Hampstead. It was a small place—just one room, really—but with a tiny garden out front. Even for a few days in London, I need a bit of green.

It sat at the end of a narrow pedestrian path, a row of small, light-filled cottages originally built as artist studios. As we were handed the keys, the owner said, “Lots of artists lived here in the 1930s.”

Later, I looked it up. We were staying in Number 7. It turned out to be the former home of Barbara Hepworth. Not just any artist—but one of the few internationally recognised women artists of her generation. A quiet kind of extraordinary.

Her life in that cottage was intense. She had a young son, an unconventional relationship, and then unexpectedly gave birth to triplets. Four children under five. A partner drifting between two homes. A coal-hole-turned-sculpture studio. It’s no surprise she fell into postnatal depression.

But her friends helped. The babies were cared for. She recovered. And her work continued. What struck me most was not just that she kept working—but how she worked.

She didn’t speak of domestic life as something that competed with creativity. For her, they were interwoven. Interdependent. And she believed that being creative every single day—no matter how small—was essential.

A sketch before bed. Arranging pebbles on the windowsill. Picking flowers from the garden.

It didn’t need to be grand. Or finished. Or public. It just needed to happen.

That changed how I thought about creativity. I’d always believed it only counted if it could be shared, exhibited, or sold. But what if it’s simply a thread that runs through the day?

Now I always have something small and steady on the go. At the moment, it’s a needlepoint cushion stitched with naturally dyed threads from The Studio. Each square takes about five minutes. Sometimes I do one. Sometimes three. But I keep the thread moving.

This rhythm—the quiet persistence of daily making—is what I want to share. Not a system. Not a productivity hack. Just space to remember what creativity feels like, even in the middle of life.

On Thursday 12 June at 11am (UK time), I’m hosting a free one-hour masterclass called About Time. It’s for anyone who wants to return to their creative self—gently, without pressure.

There will be a replay for all who register.

Innovative weaving by Elda Cecchele, Venice

After her death, the heirs of the Venetian weaver gave her entire studio contents to the Il Museo di Palazzo Mocenigo in Venice. All the photographs here were taken at the exhibition The Elda Cecchele Donation which runs until 2nd March 2025*.

Elda Pavan was born near Padua in 1915. Her father was killed in the First World War and she was largely raised by her grandparents, learning textile skills from her grandmother.

She clearly had entrepreneurial skills as in her teens she chummed up with her close friend Angela, who worked as a commercial spinner, creating household linens and selling them to shops in Padua and Venice.

In 1937, at the age of 22, she married Gino Cecchele, whose wealthy family owned a number of spinning mills in the area and had five children.

After the second world war the Cecchele mills hit financial problems and Elda’s family moved into one of the disused mill buildings in Padua. Here Elda set up a small scale workshop with a hand loom and, in 1947 she registered her business on the artisinal register as Elda Cecchele. By 1966 she had a trademark, Cecchele.

What she was now interested in was making unusual one off, artistic pieces, pushing the boundaries of what weaving meant. That meant either creating her own range or working with existing couture houses to give an edge to their ranges.

From 1947 until 1988 she worked with various Italian fashion brands, providing fabrics for clothes, bags and shoes. Her work - becoming the raw materials for named designers like Ferragamo and Cerrutti - was rarely credited, though behind the scenes she was well known and honoured at large trade events.

What I loved about the samples in the exhibition is how you can see her thinking.

She has a magpie eye for materials.

All kinds of braids, ribbons, leather strips, plastic streamers . . . .

were incorporated into fabrics without worrying about whether it was ‘the done thing’

I particularly love how she incorporates thick ready made trimmings into fabrics.

Threading dyed net and a furnishing braid through a linen woven base.

This one appeared to be plastic streamers with overlocked thread on top, threaded through a wool design.

The fabrics would then be cut up and made into clothes, bags or shoes.

Wedding dresses were particularly popular - probably because they were high ticket, special occasion outfits where laundry would not become a problem.

The fabrics were also made into simple dresses where the various woven ribbons (so like threaded nightdresses in many ways) could be mitred into straps.

And then there were some samples that were simply joyful play

If you read Italian, and are interested, an inventory of the entire collection can be downloaded here though there are not photographs of everything.

Time for an introduction

Last Friday a completely bonkers thing happened. My Friday film caught the wave of the YouTube algorithm and over the weekend 50,000 (yes fifty thousand - fifty times more than usual!) people watched it.

People from all over the world watched it, and they left comments and got in touch and it was wonderful.

So I thought that I should really do an introduction video that explains who I am, what I do and how I got here, through in incredibly wiggly career path that only now seems to be making sense.

It is also an honest account of where things have gone wrong. It is for people who have watched their dreams evaporate, people wondering whether to take the leap from a job that they no longer love, and for people who wonder if they are wandering and lost.