Journal

Why We Buy Online Courses and Never Start Them (And Why That’s Perfectly Fine)

Let me share something I’ve noticed after years of running online courses and talking with creative people: we’ve all got that folder of good intentions. You know the one – filled with courses we bought with genuine enthusiasm, promising ourselves we’d finally learn that new technique or tackle that project we’ve been dreaming about.

Then life happened, and those courses became silent witnesses to our supposed creative failures. But here’s what I’ve discovered – that story we tell ourselves about being course-collecting failures? It’s missing some important context.

The Three Types of Online Courses We Buy

After countless conversations with members of my creative community, I’ve noticed we buy online courses for three very different reasons. Understanding which category your purchase falls into can save you from unnecessary creative guilt.

1. The “Support” Purchase

This is when we buy a course primarily to support a maker whose work we value. Maybe you’ve been following someone’s YouTube channel for months, enjoying their free tutorials and insights. When they offer a reasonably priced course, you buy it – not necessarily because you need to learn that particular skill right now, but because you want to show support.

I experienced this directly when I created a charity course for making patchwork stars. People bought it knowing they already could make those stars, or knowing they’d never sewn a stitch in their lives. The point wasn’t the star – it was supporting the cause.

The key insight: You’ve already done the important work by purchasing. The guilt about not completing it? That’s the real problem, because it can actually damage your relationship with creators you genuinely enjoy supporting.

2. The “Fantasy February” Course

These are the self-paced courses we buy thinking we’ll tackle them “when things quieter down.” You know – in February, after the holiday rush. Or October, after summer chaos. We’re seduced by the mirage of empty calendar space that never actually arrives.

The truth nobody talks about? There is never going to be this open empty time. Life doesn’t work like that.

These courses trigger our deepest creative guilt because scheduling time for something we want to do (rather than need to do) feels selfish. When someone asks us to do something else during our planned “course time,” we immediately abandon our creative plans. After all, it’s just for us, right?

Two approaches that actually work:

- The skim approach: Watch the videos (perhaps on double speed) just to absorb techniques and approaches that inform your general making practice. You paid for access to knowledge – you don’t have to make the exact project to get value.

- The realistic schedule approach: Choose ONE course, calculate the actual time needed, and block it in your calendar like any other commitment. Be brutally honest about timeframes and stick to your creative appointments.

If neither approach appeals to you, consider this radical idea: delete the courses you’re not going to do, and stop buying more until you’re ready to properly schedule them.

3. The “Journey” Course

These are the substantial, community-based courses that unfold over weeks or months. They often combine making with deeper themes – the kind that promise to be transformative rather than just instructional.

The stumbling block here is feeling “behind.” Every course I’ve run or taken includes people apologizing for missing a week, convinced they’re the only ones struggling to keep up, certain they’ve blown their chance at the full experience.

Here’s what course creators won’t tell you: We expect people to miss sessions. We design for it. This isn’t school. We’re not giving out gold stars for homework completed.

The rhythm of these courses often mirrors life itself – sometimes you’re deeply engaged, sometimes you step back and observe, sometimes you jump back in halfway through. That’s not failure; that’s how humans actually learn and grow.

When Guilt Kills Creativity

The real damage happens when we carry guilt about our course-purchasing habits. Guilt kills creativity – it’s the fastest way to shut down the very exploration and joy we were seeking when we bought the course in the first place.

Your relationship with online learning doesn’t have to follow anyone else’s rules. Some courses are meant to be fully completed, others are meant to be browsed, and others are meant to be supported. The key is recognizing which is which, and releasing yourself from the obligation to treat every purchase the same way.

Creating Better Courses (And Better Relationships with Them)

These insights are shaping how I design my own courses. The next project I’m launching – called Threaded – incorporates everything I’ve learned about how people actually engage with creative learning:

- Built-in gap time so people don’t feel behind

- Regular, predictable rhythms rather than front-loaded intensity

- Permission to engage at your own level without guilt

- Community support that acknowledges real life

The course begins on the autumn equinox and explores folk tales, making, and creativity through the lens of midlife awakening. But more than that, it’s designed to work with how we actually live, not how we think we should live.

Reframing Your Course Collection

If you’re carrying guilt about unfinished courses, try this: go through that folder and categorise everything. Which ones were really support purchases? Which ones were fantasy February optimism? Which ones still call to you?

Delete without guilt. Keep without obligation. And remember – your creative journey belongs to you. There’s no wrong way to learn, and there’s no timeline you must follow except your own.

The courses will still be there when you’re ready. And if they’re not? Well, perhaps that tells you something important about what you actually needed from them in the first place.

If you’re curious about Threaded and want to hear more about this gentler approach to creative learning, you can sign up here to receive details before the course begins. And if you found this perspective helpful, I’d love to hear about your own experiences with the courses sitting in your digital library.

Studio Exclusive: Dyeing with Hollyhock, true blues

We’re always told that blue is the most difficult colour to achieve naturally. Indigo and woad are the traditional sources, but they come with their own challenges - you need masses of plant material, the fermentation process takes weeks, and there’s often some fairly unpleasant chemistry involved. For anyone working on a smaller scale, it can feel like blue is simply out of reach.

Which is why I was so surprised when I discovered black hollyhocks.

A small handful of Alcea nigra petals will give you genuine blues - not the murky greenish tones you might expect from most flowers, but clear, true blues ranging from pale denim to deep navy. It seems almost too straightforward to work, which is probably why it’s not talked about more.

Black hollyhocks might sound exotic, but they’re more ordinary than you’d think. Mine came from one of those plant racks outside a supermarket - three for a tenner. Nothing special, no hunting through specialist nurseries or ordering heritage varieties online. Just regular garden centre plants that happened to be the right ones. If you see them, snap them up.

And you only need three plants to get started. Each one will give you flowers throughout the summer, and each flower holds enough colour for small-scale dyeing projects. A few petals will tint a skein of wool, a handful will give you a deeper shade.

The process itself is refreshingly simple. No fermentation vats, no complex chemistry, no waiting weeks for results. Just flowers, heat, and fabric.

If you want to grow your own, it’s even easier than buying them - I’ll share the growing details below. But there’s something satisfying about discovering that one of natural dyeing’s most coveted colours can come from something so wonderfully unremarkable.

Studio Exclusive: Heather for Natural Dyeing: Golds and Greens

At the heart of my love for creating colour from plants is place, connection, and a spiralling back through time. A thousand years or more, to when colour was coaxed from nearby plants in much the same way as I do now. Textiles were treasured, not disposable. Colour was earned.

I am not drawn to the tidy, packaged pots of powdered dye. That is someone else’s story. Mine is rooted here, in the plants underfoot, in the scraps I gather from garden, hedgerow, kitchen, and hill. It matters to me that the colours come from this place, in this season.

It is easy to imagine the past in washed-out browns, but that is a trick of time and fading fibres. Our ancestors loved bright colour. They prized the purest yellow from weld, the deep orange from madder, the luminous blue of indigo. When cloth survives, it often shows only the gentled remains of those shades, except in the hidden seams or protected fragments, where the original garishness still sings through.

The Scottish plants I tend to use do give softer, more muted tones. Grey-pinks, olive greens, peach, silver. These are the colours I am drawn to myself. Earthy. Weathered. But in the earliest periods, these quieter plant dyes would likely have made up the whole palette. There is little evidence of access to strong imported colours in those times. What was used was what could be gathered, grown, or foraged locally.

Heather is an exception. One of the traditional dye plants of the Highlands, it offers a surprising richness. When you harvest it just before it flowers, it gives a glowing golden yellow, the kind that lifts the dullest grey and makes it sing. And it asks very little of you. Simmer the flowering tops for half an hour, add your yarn, and wait. No alchemy. Just time and heat.

Below, I have included some tips to get the most from it, more lightfast, longer-lasting shades. But honestly, even if you throw it in a pot over a campfire and stir in some fence-gathered fleece, you will get something. Some trace of colour and place.

There is a theory that the earliest tartans were not planned patterns, but checks and stripes that came from weaving together home-dyed threads. Each batch different. Each colour the result of what could be gathered that season. It rings true to me. That piecemeal beauty. That sense of the cloth being not just worn but witnessed.

That is how I work. A hundred grams of fibre at a time. No two batches quite alike. Each one a distillation of weather, landscape, and mood.

Below, you will find a simple how-to for dyeing with heather. All heathers will give you dye but the traditional one in Scotland was ling, Calluna vulgaris.

Studio Exclusive: Dyeing with Willowherb: From Bright Gold to Charcoal

Rosebay Willowherb (Chamaenerion angustifolium) is one of the most recognisable native plants in the UK, with tall spires of magenta flowers, narrow fringed leaves, and soft, smoke-like seed heads. It thrives in disturbed ground, often appearing on bombsites, railway sidings, and industrial clearances. During the Blitz, London’s bombed-out spaces famously filled with its bright pink blooms.

Though common now, it wasn’t always so. Up until the late 19th century, it was relatively rare in the UK. Its explosive spread may be the result of hybridisation with American species and its adaptability to post-industrial landscapes. Each plant can produce around 80,000 seeds, fitted with fluffy, wind-borne parachutes. They can travel up to 20 miles and remain viable for 20 years, making this one of the UK’s most persistent pioneer species. It is one of the few plants that will germinate on burnt ground.

It is not surprising that it is a symbol of resilience, rising from the ashes, a phoenix of a plant.

Despite its invasive tendencies, willowherb has a long and rich history of human use. Its young shoots, around 4 to 6 cm, can be steamed and eaten like asparagus. The early leaves were used fresh in salads. As they mature, they accumulate tannins and were traditionally fermented to make “Ivan Chai,” a herbal tea that was a major Russian export to Britain before Indian tea plantations took over the market. The plant’s stems contain a thickening agent once used to set jellies, and the magenta flowers were sometimes turned into floral syrups.

Its seeds, attached to silky fluff, were used to start fires. People kept them in small lidded containers called tinder boxes, used to store easily ignitable material for lighting fires before the invention of matches. Some accounts even claim the fluff was used to stuff mattresses, though the volume needed makes this questionable.

Medicinally, willowherb was used as an antispasmodic and for treating skin ulcers and digestive complaints. More recently, it is being investigated for its potential use as a renewable biomass fuel.

And - of course - it is a spectacular natural dye plant.

The reason willowherb can be fermented into tea lies in its high tannin content - but unlike many plants with tannins that produce various shades of brown, willowherb gives a surprising yellow. And, when combined with iron, the tannins react and the yellow transforms into a deep charcoal.

It’s this dramatic shift that makes it such an exciting plant for creative dyeing, perfect for layered, expressive effects in natural textiles. Dip dyeing, tie dyeing, . . . .

Rag Rugs, Remembered: Creativity, Memory, and the Quiet Legacy of Women’s Work

There’s something deeply evocative about a rag rug.

For me, they conjure childhood memories—of my gran cutting up old clothes in her Northeast home, of hands busy at the hearth as winter crept in. Every year, she’d make a new rug. Not as art, but as necessity. And yet, looking back, it was art. Quiet, domestic, fiercely resourceful art.

Rag rugs are humble. Scraps turned into something sturdy, beautiful, and useful. And lately, my fingers have been itching to make one. Partly due to the powerful exhibition I saw recently—Winifred Nicholson: Cumbrian Rag Rugs at the Tullie Museum in Carlisle—and partly because I’ve inherited my gran’s rug frame. A piece of family history, waiting to come alive again.

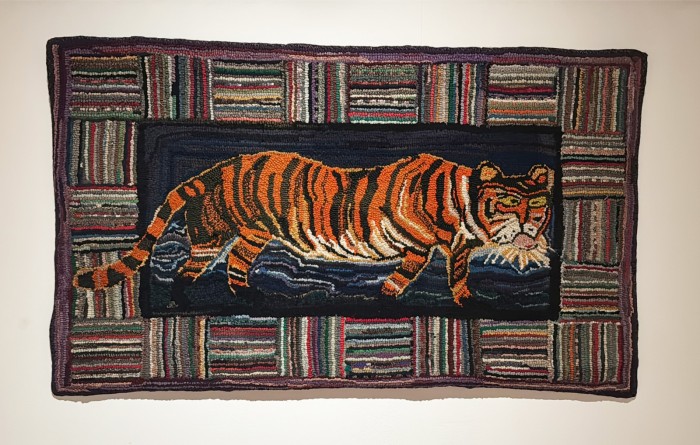

Tiger, worked by Janet Heap early 1960s

A Different Kind of Creativity

The exhibition explores how Winifred Nicholson—a respected artist—collaborated with rural Cumbrian women from the 1920s through the 1980s to create striking rugs. Though Nicholson provided loose design ideas, the true artistry lay in the hands of makers like Mary Buick. Her work, full of precision and pictorial nuance, told stories through stitches. Yet in art history, her name is often lost behind Nicholson’s.

This discrepancy matters.

It reflects how society has long undervalued women’s domestic creativity. Rug-making, quilting, embroidery—seen as craft, not art. Functional, not visionary. And yet, these works were acts of deep care, resourcefulness, and yes—creative genius.

Sheep, worked by Mary Bewick to design by Winifred Nicholson 1960s

Making With What You Have

British rag rugs evolved from scarcity. No pre-planned palettes or bought-in fabrics—just old coats, worn sheets, a t-shirt you no longer needed. In the Northeast, these were called clippy mats or proggy rugs, and they followed simple geometric designs. My gran always used diamonds—drawn on old hessian sacks, filled in with whatever colours were on hand.

In contrast, American traditions turned rug making into a designed-from-scratch craft. But in the UK, it was about making do. And in that “making do,” women made beauty.

Tractor and Haycart, worked by Mrs Hall to design by Jovan Nicholson 1967

Creativity as Reclamation

Watching the exhibition’s rugs—some damaged, worn, obviously lived with—was unexpectedly moving. They hadn’t been preserved behind glass. They’d been stepped on, warmed toes, sat beside fires. They were loved, and used, and that’s part of their magic.

It reminded me that creativity doesn’t need polish. It needs space. Time. Willing hands.

And it reminded me that our making—however small or irregular—is a way of reclaiming ourselves. Especially for women whose time, historically and still, has so often been claimed by others.

What’s Next

I’ll be making my own rug soon. I don’t have long strips of wool, so it’ll be a clippy mat—shaggy, abstract, full of texture and colour. I’ll be working with what I have, like my gran did. Like so many did.

If you’ve made a rug, or remember someone who did, I’d love to hear. If you’ve been to the exhibition, let me know what stayed with you. Creativity is always richer when it’s shared.