Journal

Do Plant Dyes Fade? Two Chair Seats, 100 Years Apart

The first question people ask about botanical dyes is whether they fade.

My answer: yes, they do. All dyes fade. But if you prepare your fibres properly and choose your plants sensibly, natural dyes will not fade any more than most synthetic dyes. Often they’ll fade considerably less.

Here’s the evidence from my collection.

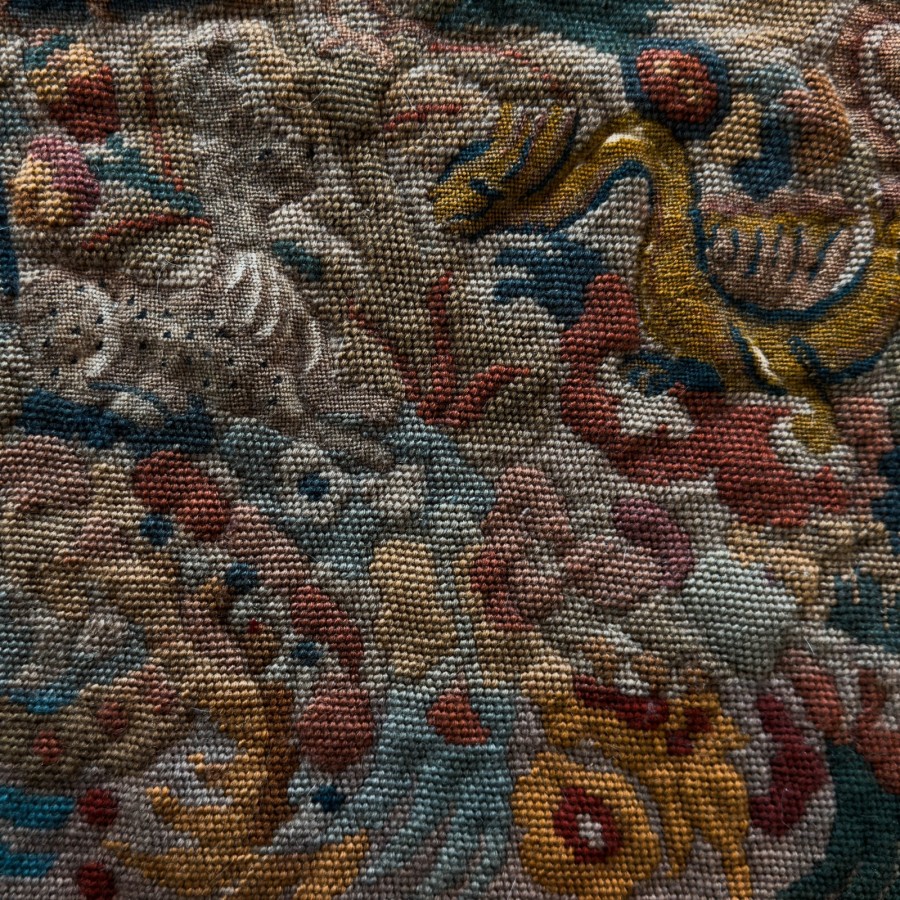

The 18th Century Piece: 1760s-1790s

This needlepoint was made as a chair seat, probably between 1740 and 1770. It’s worked in plant-dyed wool on even-weave linen - petit point at 22 stitches per inch for the animals, tent stitch at 11 stitches per inch for the background.

This was a working chair seat. It wasn’t wrapped in tissue and kept in a drawer. It was sat on, used, eventually removed from the chair when it wore out or the furniture was updated.

It’s approximately 250 years old.

When you compare the front and the back, you can see some fading - the colours have lightened. But they haven’t changed. The blues are still blue, the rusts still rust, the greens still green. The colour relationships remain intact. You can still read the design clearly.

The silk stitches have disappeared almost entirely - silk is more vulnerable to wear than wool - but the wool has survived with its colours stable.

The 19th Century Piece: 1860s-1880s

This is Berlin woolwork, probably made between 1860 and 1880. It came from a prayer chair, worked on the new double-thread canvas that made following printed patterns easier for amateur needleworkers.

It’s dyed with early aniline dyes - synthetic dyes that were revolutionary when they arrived. Bright turquoises, sharp vermilions, colours that were difficult or impossible to achieve with natural dyes.

The bottom section was hidden in the chair structure and never saw daylight. You can see what those colours originally looked like - that intense turquoise, those vivid reds.

The exposed section tells a different story. Everything has faded to murky beiges and washed-out pinks. The colour relationships have collapsed. The design is harder to read.

This piece is roughly 150 years old - a full century younger than the plant-dyed chair seat.

What This Tells Us

The problem with early aniline dyes wasn’t that they were synthetic. It was that the dyers hadn’t yet figured out lightfastness. They were chasing novelty and brightness, not durability. Contemporary accounts mention these dyes fading after a week in a shop window.

The 18th century chair seat was made by someone who expected it to last. Proper mordanting, stable dye plants, good materials. The dyer knew what they were doing.

The Practical Takeaway

Fading isn’t about natural versus synthetic. It’s about technique, mordanting, and choosing stable dyes.

The workhorses of 18th century dyeing - indigo, woad, madder, weld - were stable precisely because they’d been refined over centuries of use. Dyers knew how to prepare fibres properly, which mordants to use, which plants gave lasting colour. Many other plants, local plants, are fantastic dye plants too. The difference isn’t the plant, it’s the preparation.

If you’re working with botanical dyes now, you have access to that accumulated knowledge. Proper mordanting, good fibre preparation, and careful technique will give you lasting colour from all sorts of plants. Start with what’s growing around you. Use mordants. Experiment and take notes. The colours will last.

The Problem with “Play” in Creativity (And What It Actually Means)

A few weeks ago, someone in The Studio brought a perfectionism problem to our Friday gathering. She couldn’t start projects, or if she did, she felt she’d already ruined them before she’d really begun. Everyone offered advice, and the same word kept coming up: “Play. Just play with it.”

But I noticed I was having a strong physical reaction to that word. It conjured up bright colours, noise, children’s TV energy - everything that makes me uncomfortable. So I went for a walk to figure out what was going on.

Turns out, my understanding of creative play was completely wrong - or at least unnecessarily narrow.

What Play Actually Means

Play in making isn’t about being loud or messy or forcing yourself to be spontaneous. It’s simpler than that: making something with no set outcome, no purpose to measure against, and therefore no way to be perfectionist about it.

In this week’s Friday Film, I share three real examples from Studio members showing what this looks like in practice:

- Making quilts in deliberately uncomfortable colours

- Drawing with your non-dominant hand to see what emerges

- Understanding that nobody else knows what you were trying to make

Plus the story of my embroidered duck that, according to my friend, looks like it’s been run over. She’s not entirely wrong.

Watch: Creative Play & Perfectionism

If you struggle with perfectionism or getting started on creative projects, this might help. It’s not about adding another practice to your day - it’s about recognizing the play that’s probably already there in your making.

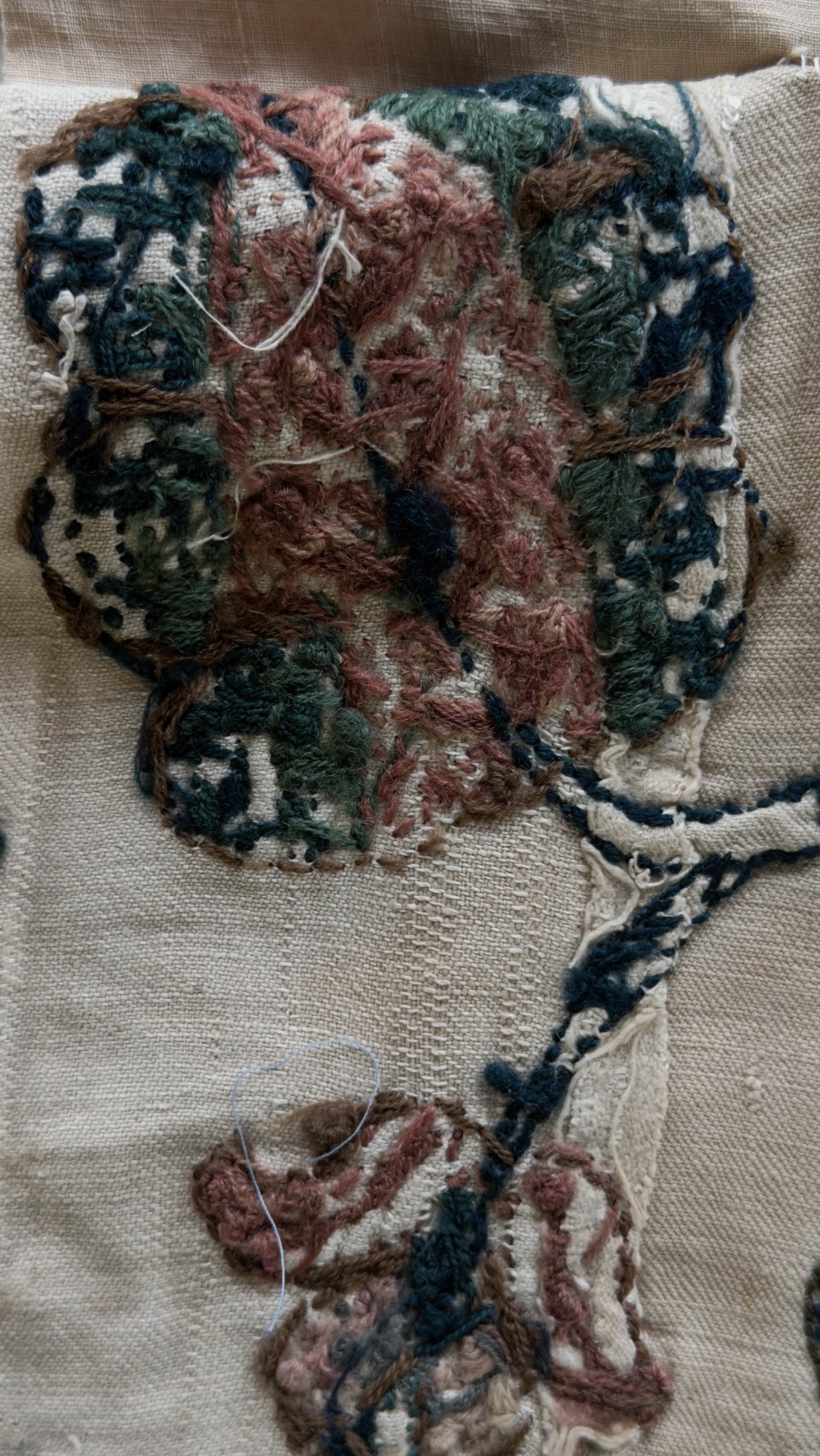

Crewel work fragment from Jacobean Bed hangings: What You Can Still See After 400 Years

A couple of months ago I bought this piece of embroidery as a study piece for The Studio. It’s a fragment of what was once a bed curtain, designed for privacy and warmth in a cold English manor house. About forty centimetres square, embroidered in crewelwork – plant-dyed wool on a linen (or possibly linen-cotton) twill. It dates from around 1610 to 1620.

The design is the Tree of Life, newly popular at the time as more and more designs from India reached England via the East India Company, founded in 1600. The curving branches and scrolling leaves you can see here would have extended from the bottom of the curtain right to the top. The ground may have had plants and animals amongst the trunks.

Because this is a fragment, a study piece, we can see the back – and this is where it gets interesting. The back would have been out of direct light, protected by the folds of the curtain. The threads haven’t faded much. The indigo blues are the same front and back. The browns too. The only colour change is from a deep pinky fawn to something paler.

That tells you which dyes lasted and which didn’t. Indigo – imported from India by the early 1600s – doesn’t fade. The browns, likely from oak bark or walnut hulls, held their colour. But that pinky fawn has shifted, lost its intensity where light could reach it.

The design was drawn onto the seamed linen. You can see the uncovered lines in some of the photos – places where the embroiderer didn’t quite cover the guide marks. Perhaps it was drawn freehand by the maker, or by a professional embroidery designer. Or perhaps it came from prick and pounce – a large-scale master drawing, the lines perforated with needle dots, fine charcoal or dried cuttlefish ink forced through the holes onto the fabric below.

The embroidery was probably done by the women of the household, though professional embroiderers did exist. A full set of bed hangings, creating a room within a room, would have taken up to fifty yards of fabric. It was likely a project worked on by many hands.

Bed hangings weren’t decorative extras. They were essential household equipment. When pulled closed around a bed, they gave warmth and privacy in houses without central heating, in rooms where multiple people slept. Even wealthy households had servants sleeping in the same rooms as their employers. The hangings were often worth more than the wooden bed frame they decorated.

What remains in this fragment: the blues that lasted, the fawn that faded, the visible design lines someone drew four hundred years ago, the way stitches follow curves and fill shapes, the seam where two pieces of linen were joined to make fabric wide enough for a bed curtain.

And at the back, protected from light all these years, something close to the original colours.

Looking closely at pieces like this is what we do in The Studio – investigating how things were made, working with traditional techniques, making with intention. More about The Studio here.

Bundle dyeing yarn: a November experiment

The yarn waits bundled with gathered leaves while frost writes temporary stories along the hedgerows and November light shifts from copper to rose-gold across the valley.

Everything transforms in its own time: raw materials and fleeting moments both becoming something we can hold onto.

What Remains: Looking at the Things People Actually Used

Last Sunday, I sat in an archive room with a 16th-century nightshirt spread in front of me. Twenty minutes, just looking. The archive assistant had shown me how to wash my hands properly, how to handle the fabric, and then left me alone with this thing that had clothed someone’s body hundreds of years ago.

It wasn’t pristine. That’s why I’d chosen it.

Most museum collections preserve the best of things - the ceremonial robes, the unworn wedding dress, the sampler framed and protected by seven generations of careful daughters. These objects tell us about aspiration, about wealth, about what people thought worthy of keeping. But they rarely tell us about Tuesday afternoons or mending by candlelight or the third time you patched something because cloth was too precious to discard.

This shirt told a different story.

What We Don’t Usually Get to See

The V&A’s new storehouse in east London has done something quietly revolutionary. Instead of keeping their vast collections locked away - the usual museum problem where 95% of holdings never see daylight - they’ve opened the stores to anyone who wants to book an appointment. No academic credentials required. No research proposal. Just curiosity.

I went online, scrolled through their catalogue like a particularly sophisticated version of window shopping, and selected five objects. Four were early embroidered bags for research - we’re making bags in The Studio this month, and I wanted to see what real medieval and Renaissance pouches actually looked like, not the romanticised Pinterest versions. The fifth was this shirt.

The V&A catalogue described it simply: linen, silver thread embroidery, handmade lace inserts, probably late 16th century. What the catalogue didn’t say - what catalogues never quite capture - was that someone had loved this thing enough to keep mending it long after it stopped being beautiful. Patching, altering, reusing

The Evidence of Use

Both cuffs had been patched, where the wearer’s wrists had worn through the original embroidery. The patches used similar silver thread but in slightly different patterns - perhaps done years apart, perhaps by different hands. The underarm gussets had been replaced entirely, more than once. There was a hole at the front that had never been mended, and a dark stain on one sleeve that might have been blood.

This was a high-status garment. The quality of the original work, the silver thread, the fine linen - this belonged to someone with means. But it had been worn, properly worn, the kind of wearing that requires maintenance and repair. And someone - we don’t know who - cared enough to keep mending it.

I kept thinking: what would it take for something like this to survive 400 years? Someone had to decide it was worth keeping even after it was too damaged to wear. Someone else had to store it carefully. Multiple someones had to choose not to discard it, cut it up for cleaning rags, or let it moulder in a damp chest. And eventually, someone had to give or sell it to a museum.

Most things don’t survive. Most of what people made and used and wore out is simply gone. What remains is either the too-precious-to-use or, more rarely, something like this - precious enough to keep but used enough to show us what real life looked like.

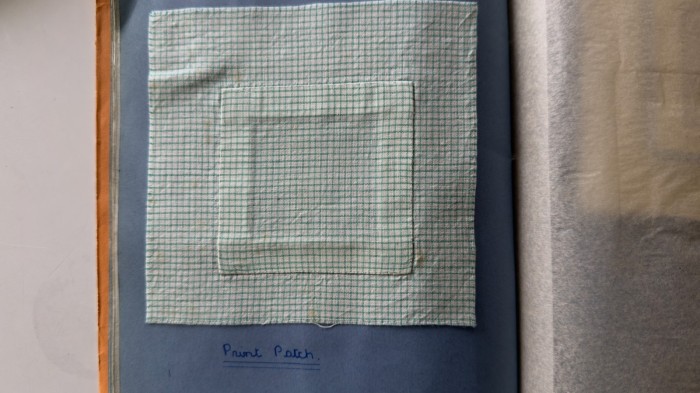

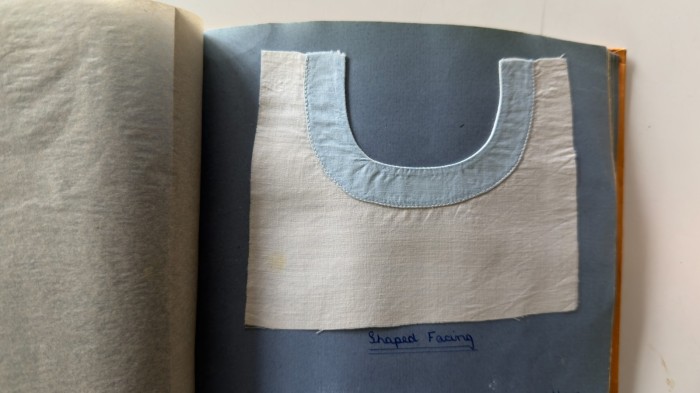

Maureen’s Exercise Book, 1947

When I got home, I pulled out something I’d bought on Vinted last month: a sewing exercise book from a finishing school, dated 1947. The young woman who made it - Maureen Bushell - had filled it with samples. Hemming, darning, inserting gussets, making buttonholes, patching knees, all the skills that would have been considered essential for a woman of her time.

1947 is an interesting year to be learning these skills. The war had been over for two years, but Britain’s economy was in tatters. Clothing rationing, which had begun in 1941, had actually intensified. Each person got 66 coupons a year, and a dress cost 11 coupons, a blouse 5, a pair of stockings 2. Women’s magazines ran endless features on making do and mending, turning old coats into skirts, unpicking jumpers to reknit them in fashionable styles.

So Maureen, at finishing school (which suggests her family had some means), was learning skills that had suddenly become relevant again across all social classes. The ability to darn invisibly, to patch neatly, to alter and remake - these weren’t genteel accomplishments anymore. They were survival skills.

What strikes me about her samples is their skill. This is work that would have been considered merely adequate at the time - I’ve been told she regarded herself as a mediocre needlewoman - but it’s far beyond what most of us could do now. The tension is even, the stitches regular, the corners properly mitred. This was baseline skill, what every woman was expected to master.

Seventy-seven years later, so many of us couldn’t darn a sock if our lives depended on it.

Why Looking Matters Now

There’s something that happens when you spend real time with a handmade object. Not glancing, not photographing for Instagram, but actually looking. Twenty minutes with the nightshirt. An hour with Maureen’s exercise book, turning pages slowly, noticing where her stitching gets tighter or looser, where she’s made a mistake and corrected it, where you can almost feel her frustration or satisfaction.

You start to see the hands. You start to notice mood - the careful sample done when she was fresh, the slightly rushed one done at the end of a long day. You see decisions: where to start the patch, which direction to run the darn, whether to unpick and redo or just carry on.

This kind of looking is harder than it sounds. We’re trained to glance and move on, to consume images quickly, to form instant opinions. Sitting with one object for twenty minutes feels almost transgressive. Your mind wanders. You get restless. You think you’ve seen everything there is to see.

And then, if you keep looking, things begin to reveal themselves. The nightshirt’s bloodstain becomes a person’s wound. The patched gussets become evidence of someone’s decision that this was worth saving. Maureen’s ever so slightly wobbly hemstitch becomes the hand of a young woman learning, probably bored, possibly hungry (1947 had food rationing too), definitely not imagining that seventy-seven years later someone would be looking at her work and thinking about her life.

An Invitation

You probably have something in your home that deserves this kind of attention. Something handmade, handed down, or made so long ago it almost feels like someone else made it. Find it. Clear some space. Turn off your phone. And just look.

Look past what you think you already know about it. Look at tension in stitches, mistakes corrected or left visible, places where the maker changed their mind or persevered despite difficulty. Look at wear patterns, stains, repairs. Look until you can almost feel the hands that made this, the mood they were in, the decisions they made.

This isn’t precious or spiritual - though it might feel like both. It’s just the kind of attention that handmade things have always deserved and rarely received. The kind of looking that connects us back through time to all the people who made and mended and kept things going, whose names we mostly don’t know, whose work mostly didn’t survive.

But some of it did. And it’s still here, waiting to be really seen.

Visit the V&A Storehouse: You can book appointments online - remarkably underused and absolutely worth the trip

Join us in The Studio: This season we’re making bags inspired by Irish traveller tales.